Structure and Mechanism of TAK-243 (MLN7243) in E1 Activating Enzyme Inhibition

While surgical and radiological interventions focus on physical reduction of tissue, molecular research is exploring the inhibition of key enzymatic pathways to control cell proliferation. Central to this field is TAK-243 (MLN7243), a first-in-class, small-molecule inhibitor that targets the Ubiquitin-Activating Enzyme (UAE or UBA1), the primary E1 enzyme in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. By forming a stable TAK-243-ubiquitin adduct, it blocks the first step of the ubiquitin cascade, leading to a depletion of ubiquitin conjugates and inducing catastrophic proteotoxic stress. This mechanism is particularly relevant in the study of hyperproliferative conditions, where disrupting cellular homeostasis through TAK-243 (MLN7243) may offer insights into non-invasive pharmacological control.

BACKGROUND: Efforts to develop alternatives to surgery for management of symptomatic uterine fibroids have provided new techniques and new medications. This review summarizes the existing literature on uterine artery embo- lization (UAE) and investigational studies on four newer approaches. METHODS: PubMed, Cochrane and Embase were searched up to December 2007. Studies reporting side-effects and complications and presenting numerical data on at least one outcome measure were included. RESULTS: Case studies report 50 – 60% reduction in fibroid size and 85 – 95% relief of symptoms following UAE. The largest of these studies reported an in-hospital complication rate of 2.7% (90 of 3041 patients) and a post-discharge complication rate of 26% (710 of 2729 patients). Eight studies compared UAE with conventional surgery. Best evidence suggested that UAE offered shorter hospital stays (1 – 2 days UAE versus 5 – 5.8 days surgery, 3 randomized controlled trials (RCTs)) and recovery times (9.5 – 28 days UAE versus 36.2 – 63 days surgery, 3 RCTs) and similar major complication rates (2 – 15% UAE versus 2.7 – 20% surgery, 3 RCTs). Four studies analysing cost-effectiveness found UAE more cost-effective than surgery. There is insufficient evidence regarding fertility and pregnancy outcome after UAE. Five feasibility studies after transvaginal temporary uterine artery occlusion in 75 women showed a 40 – 50% reduction in fibroid volume and two early studies using magnetic resonance guided– focused ultrasound showed symptom relief at 6 months in 71% of 109 women. Two small RCTs assessing mifepristone and asoprisnil showed promising results. CONCLUSIONS: Good quality evidence supports the safety and effectiveness of UAE for women with symptomatic fibroids. The current available data are insufficient to routinely offer UAE to women who wish to preserve or enhance their fertility. Newer treatments are still investigational.

Keywords: embolization; fibroid; focused ultrasound; medical therapy;

Introduction

Uterine fibroids are the most common female pelvic tumour, typically reported to occur in 20 – 40% of reproductive aged women, and up to 70% of white and 80% of black women by the age of 50 years (Baird et al., 2003). Most fibroids are asympto- matic, but nearly half of women with fibroids have significant and often disabling symptoms including heavy menstrual bleeding, pain and pressure symptoms (Baird et al., 2003). Traditionally, symptomatic fibroids have been treated with myomectomy or hys- terectomy performed by laparotomy (Matchar et al., 2001). In an effort to reduce the cost, morbidity and lifestyle impact of major surgery, various less invasive surgical procedures, including mini- laparotomy and operative endoscopy, have been introduced over the years, but these are only applicable in a minority of cases (ACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology, 2001).

Over the last few years a variety of new treatment approaches have become available to women with symptomatic fibroids. Undoubtedly the most significant therapeutic innovation has been the advent of uterine artery embolization (UAE) as a form of non-surgical management. New technology has provided additional minimally invasive options such as percutaneous laser ablation, cryoablation, transvaginal uterine artery occlusion and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-guided focused ultrasound that are currently under intense investigation. Furthermore, new medications have been introduced, that show promise for practi- cal, long-term medical therapy for symptomatic fibroids. The objective of this review is to summarize the published lit- erature on three of the latest fibroid therapies—UAE, transvaginal uterine artery occlusion and MRI-guided focused ultrasound— with special focus on the evidence concerning the benefits and risks of these minimally invasive options. We will also provide a summary of the available clinical data on two novel medical therapeutics for fibroid treatment—mifepristone and asoprisnil.

Literature search criteria

A systematic literature search was conducted using three standard electronic databases—PubMed, Cochrane Collaboration resources and Embase. All computerized searches were performed using the Medical Subject Heading terms ‘UAE’, ‘transvaginal uterine artery occlusion’, ‘MRI-guided focused ultrasound’, ‘focused ultrasound surgery’, ‘medical therapy’, ‘mifepristone’, ‘asoprisnil’ and ‘fibroid* or leiomyoma* or leiomyomata*’ and publication type ‘clinical trial’. The search was performed in December 2007 for all available papers, and the articles selected had to be written in English. All bibliographies were cross-referenced to identify additional perti- nent studies. Letters and editorials were excluded. Studies were included if they were clinical in nature, measured fibroid-specific symptoms and uterine and/or fibroid sizes before and after treatment, reported side-effects and complications associated with treatment and presented numerical data on at least one outcome measure. We did not perform meta-analytic techniques to summarize treatment outcomes because of individual study variation in outcome measures.

Uterine artery embolization

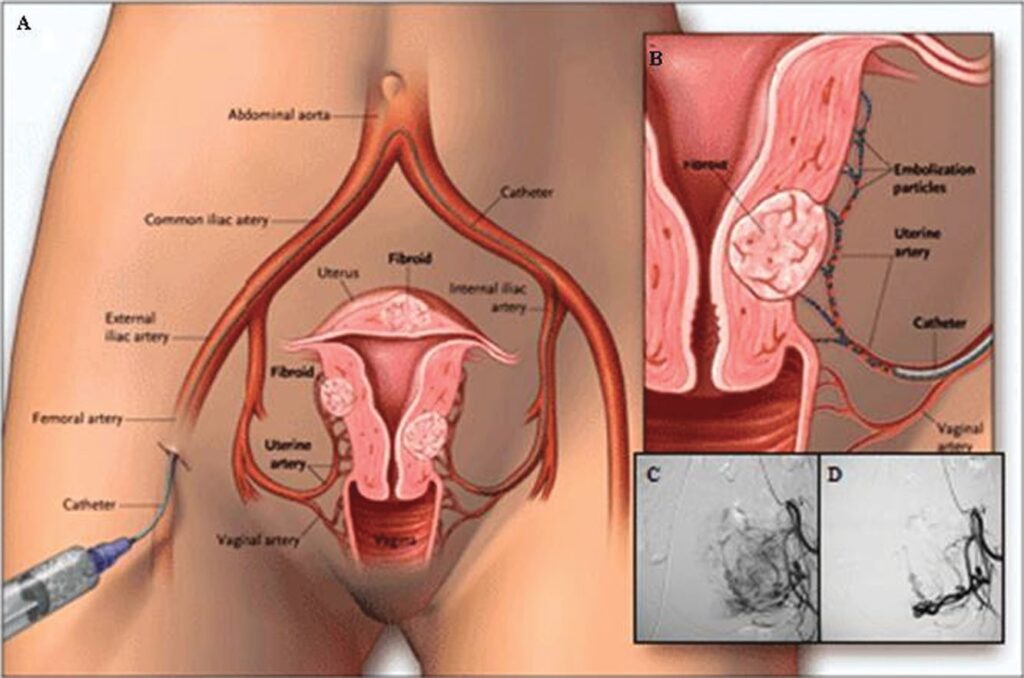

UAE is a percutaneous, image-guided procedure which is per- formed by a properly trained and experienced interventional radi- ologist (Spies and Sacks, 2004). In essence, it involves the placement of an angiographic catheter into the uterine arteries via a common femoral artery approach and injection of embolic agents (in most cases, polyvinyl alcohol particles or tris– acryl gelatin microspheres) into both uterine arteries until the flow becomes sluggish (Fig. 1) (Ravina et al., 1995; Hutchins et al., 1999; Spies et al., 1999; Pelage et al., 2000; Walker and Pelage 2002; Pron et al., 2003a; Spies et al., 2004a). The proposed mechanism of UAE’s action is that occluding or markedly reducing uterine blood flow at the arteriolar level will produce an irreversible ischaemic injury to the fibroids, causing them to undergo necrosis and shrink, while the normal myome- trium is able to recover (Aitken et al., 2006; Banu et al., 2007).

The procedure, which is usually performed under intravenous conscious sedation, generally requires ~1 h to complete. With operator experience and proper technique, patient radiation exposure during UAE is comparable to that received during routine diagnostic imaging procedures (Andrews and Brown, 2000; Nikolic et al., 2000; Zupi et al., 2003; White et al., 2007). Immediately after the end of the procedure, most patients experience moderate-to-severe ischaemic pain for 8 – 12 h— usually requiring parenteral analgesia (narcotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs)—but pain severity gradually decreases during the next 12 h (Worthington-Kirsch and Koller, 2002a,b), and a day-case or overnight stay is required at most. Recovery is typically brief and relatively mild, with 4 – 5 days of recurrent uterine cramping and constitutional embolization symp- toms (generalized malaise, fatigue, nausea and low-grade fever).

Figure 1: The UAE procedure.

Drawings (A) and (B) illustrate the path of the catheter to deliver embolization particles to occlude the uterine arteries. Angiograms show the fibroid blood supply before (C) and after (D) UAE. Patients can usually return to normal activities within 8 – 14 days (Spies et al., 2001a; Walker and Pelage, 2002; Pron et al., 2003b; Bruno et al., 2004; Worthington-Kirsch et al., 2005).

Clinical outcomes

Since it was first described in 1995 (Ravina et al., 1995), UAE for fibroids has been shown in several large case series to be effective in substantially reducing the fibroid size (on average by 50 – 60%) and relieving bleeding and other fibroid-related symptoms, with reported overall success rates ranging from 85 to 95% at short- and mid-term follow-up (Worthington-Kirsch et al., 1998; Goodwin et al., 1999; Hutchins et al., 1999; Pelage et al., 2000; McLucas et al., 2001a; Spies et al., 2001a; Katsumori et al., 2002; Walker and Pelage, 2002; Watson and Walker, 2002; Pron et al., 2003a; Spies et al., 2005a; Lohle et al., 2006). All these studies also reported high rates (87 – 97%) of patient satisfaction with outcome, measured at various points in time and along varied scales.

The studies in which UAE outcomes were evaluated with the use of a validated instrument, the uterine fibroid symptom and quality of life (QOL) questionnaire (UFS– QOL) (Spies et al., 2002a), reported significant improvements in fibroid-specific symptoms and health-related QOL measures up to 3 years after the procedure (Smith et al., 2004; Spies et al., 2005a; Scheurig et al., 2006; Goodwin et al., 2008).

Longer-term outcome data have been recently published with three prospective trials with follow-up periods exceeding 5 years (Spies et al., 2005b; Katsumori et al., 2006; Walker and Barton- Smith, 2006). These studies reported rates of symptom control after UAE ranging from 84 to 97% at 1 year and from 73 to 89.5% at 5 years (Spies et al., 2005b; Katsumori et al., 2006; Walker and Barton-Smith, 2006). These data suggest that, although there is some decline in the improvement percentage over time, levels of symptom control after UAE remain high in the long-term.

Complications

Reported complication rates of UAE are low. In a single-centre prospective study of 400 consecutive patients, the overall morbid- ity rate, using the American College of Obstetricians and Gynae- cologists (ACOG) quality indicators for perioperative morbidity, was 5% (Spies et al., 2002b). Most complications were minor and occurred during the first 3 months after the procedure. There were five (1.25%) major complications, one of which (0.25%) required hysterectomy. The FIBROID registry, the largest pro- spective study published to date, reported an in-hospital compli- cation rate of 2.7% (90 of 3041 patients), with a 0.6% rate of major adverse events (e.g. re-admission, major therapy, unplanned increase in care, or permanent adverse sequelae) and a post- discharge complication rate of 26% (710 of 2729 patients), with a 4.1% rate of major adverse events (Worthington-Kirsch et al., 2005). A relatively common complication of UAE is vaginal expulsion of an infarcted fibroid, with a reported rate of up to 10% (Spies et al., 2002b; Walker and Pelage, 2002). This complication is more frequently seen in patients with submucosal fibroids or intra- mural fibroids with a submucosal component. Expulsion most often occurs within 6 months after the procedure, but there are reports of this event after a period of time as long as 4 years (Marret et al., 2004). In most cases, the infarcted fibroid is expelled spontaneously (Fig. 2), and no additional treatment is necessary. Hysteroscopic resection or dilation and curettage is reserved for cases in which the fibroid is only partially infarcted and remains firmly attached to the uterine wall due to the increased risk of secondary infection (Spies et al., 2002b; Marret et al., 2004; Rajan et al., 2004).

When uncomplicated, fibroid expulsion can restore the uterine anatomy to nearer normal more rapidly than otherwise (Felemban et al., 2001; Gulati et al., 2004; Kroencke et al., 2003; Hehenkamp et al., 2004; Park et al., 2005). In a minority of cases, however, retention of necrotic fibroid tissue may result in chronic vaginal discharge due to shedding of fibroid material into the endometrial cavity (Walker et al., 2004; Ogliari et al., 2005). This condition can be treated effectively by hysteroscopic resection of the necro- tic fibroid material (Walker et al., 2004).

The most serious, although rare, complication of UAE is the occurrence of intrauterine infection, which has been reported in less than 1% of procedures (Hutchins et al., 1999; Spies et al., 2001a,b; Walker and Pelage, 2002; Pron et al., 2003b; Worthington-Kirsch et al., 2005). If left untreated or refractory to antibiotics, uterine infection can lead to sepsis and the need for emergency hysterectomy (Aungst et al., 2004; Nikolic et al., 2004). Two deaths from uterine infection and overwhelming sepsis have also been reported after UAE (Vashist et al., 1999; de Block et al., 2003).

Specific risk factors for this potentially life-threatening compli- cation have yet to be determined. Clinical experience and evidence from a case report (Vashist et al., 1999) suggest that infection may originate from the vagina and/or the urinary tract, which under- lines the importance of pre-procedure screening for genitourinary infection. There is also evidence that certain pre-existing con- ditions, such as a coexistent adnexal pathology (Nikolic et al., 2004), and some minor post-procedure complications, in particular fibroid expulsion (Spies et al., 2002b; Marret et al., 2004), are associated with a higher risk of infection.

Results of a retrospec- tive analysis of 414 UAE procedures showed that, although the occurrence of infection after UAE tended to be associated with the presence of submucosal fibroids, the association was not stat- istically significant in multivariate analysis (Rajan et al., 2004). In addition to two deaths from septic shock (Vashist et al., 1999; de Block et al., 2003), other three deaths following UAE have thus far been reported, one from pulmonary embolism (Lanocita et al., 1999) and two from uncertain causes (Worthington-Kirsch, 2002), in more than 100 000 procedures performed worldwide. If we assume that all these deaths were related to the procedure, the mor- tality risk would be 0.05:1000, which compares favourably with the estimated mortality rate of ~0.38:1000 following hysterectomy for non-obstetric benign disease (Maresh et al., 2002).

Treatment failure

Individual study variations in the definition of UAE failure (symptom persistence, or recurrence, or need for additional therapy) and in the period of reporting for failures make results difficult to compare between different study cohorts. Large case series with less than 2 years of follow-up reported rates of treat- ment failure, defined as the need for subsequent interventions, ranging from 5.5 to 9.5% (Walker and Pelage, 2002; Spie et al., 2005a; Huang et al., 2006). Recently published data on 1278 patients completing 36-month follow-up in the FIBROID registry showed that during the course of the study, hysterectomy, myo- mectomy or repeat UAE were performed in 9.8, 2.8 and 1.8% of the patients, respectively (Goodwin et al., 2008). Longer-term pro- spective studies reported re-interventions rates at 5 years ranging from 12.7 to 21%, with rates of hysterectomy varying from 3 to 17.8% (Spies et al., 2005b; Walker and Barton-Smith, 2006; Kat- sumori et al., 2006). In comparison, reported 5-year crude rates of re-interventions after abdominal myomectomy ranged from 8.6 to 55.1%, with crude rates of hysterectomy varying from 4.3 to 26.7% (Fauconnier et al., 2000).

There are several possible reasons for UAE failure. First, since the procedure causes fibroid shrinkage but preserves normal uterine tissue, it is possible that new fibroids will develop and symptoms recur. The risk of fibroid recurrence after embolization has not yet been defined. A prospective study using transvaginal ultrasound reported appearance of new fibroids in 8.2% (7 of 85) of patients at a median of 30 months after the procedure (Marret et al., 2003).

On the other hand, results from MRI follow-up examinations up to 3 years after UAE indicated that many clinical recurrences were not caused by development of new fibroids but related to re-growth of incompletely infarcted fibroids (Pelage et al., 2004). Incomplete fibroid infarction is most often related to tech- nical aspects of the procedure such as the presence of collateral blood supply to the fibroids (usually from the ovarian arteries) or difficulties in cannulating both uterine arteries as a result of ana- tomical variation, arterial spasm, or current use of a gonadotropin releasing-hormone agonist (GnRH-agonist) (Spies, 2003).

Successful embolization of only one uterine artery is generally regarded as a technical UAE failure as, in most cases, both uterine arteries contribute to the fibroid blood supply (Spies, 2003). Data from clinical trials support a relationship between unilateral UAE and the risk of treatment failure (Smith et al., 2004; Spies et al., 2005a; Gabriel-Cox et al., 2007).

One study of 81 UAE patients, of whom seven received unilateral embolization, reported a trend toward needing additional treatment if bilateral UAE was not performed (Smith et al., 2004). In multivariate analysis of 1701 UAE procedures, the FIBROID registry reported a negative effect on symptom scores at 6 and 12 months for patients who had unilateral embolization (Spies et al., 2005a). More recently, a study of 562 UAE patients, of whom 33 (5.9%) had unilateral embolization, reported that women receiving unilateral UAE were 2.2 times more likely to undergo hysterectomy by 5 years than those having bilateral embolization (Gabriel-Cox et al., 2007). Unilateral UAE remained a significant predictor of sub- sequent hysterectomy even after controlling for age in multivariate analysis (Gabriel-Cox et al., 2007).

Studies assessing the effect of baseline uterine characteristics on the likelihood of treatment failure reported conflicting results: three studies found no relationships between uterine or fibroid size and the risk of failure (McLucas et al., 2001a; Katsumori et al., 2003; Huang et al., 2006), whereas other studies reported that larger fibroid size and higher fibroid number were significant predictors of failure (Marret et al., 2005; Spies et al., 2005a; Isonishi et al., 2007; Goodwin et al., 2008).

Studies also found that a history of prior fibroid surgery signifi- cantly increased the risk of failure (McLucas et al., 2001a; Huang et al., 2006).

Coexisting pelvic diseases may also increase the chance of treatment failure. Although no studies have specifically assessed the relationship between undiagnosed concomitant adenomyosis and the incidence of clinical failure of UAE, adenomyosis was detected on histopathologic examination in up to 36% of uteri removed after embolization because of symptom persistence or recurrence (McLucas et al., 2002; Marret et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2006; Gabriel-Cox et al., 2007).

Other comorbidities that can predispose patients to a poor clini- cal outcome include endometriosis and ovarian cysts, that may be a cause of persistent pain after UAE, and chronic salpingitis and endometritis that may increase the chance of life-threatening infection (Hovsepian et al., 2004).

There is no doubt, therefore, that appropriate patient selection is crucial for obtaining a successful outcome from this therapy. On the basis of reports of expert committees, supplemented by evi- dence from clinical trials, UAE should only be considered for women with significant symptoms (bleeding, pain and/or pressure symptoms) specifically attributable to uterine fibroids who might otherwise be advised to have surgical treatment (Hovsepian et al., 2004; ACOG Committee Opinion, 2004; SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines, 2005; National Institute for Health and Clini- cal Excellence, 2007). The ideal candidates are women who no longer desire fertility but wish to avoid surgery and/or retain their uterus or are poor surgical risks. Embolization is also an excellent option for patients who will not accept blood transfu- sions and for those who are severely anaemic and require immedi- ate intervention. Current advice is that UAE should not be offered to asymptomatic women or to women whose only fibroid-related complaint is infertility (Hovsepian et al., 2004; ACOG Committee Opinion, 2004; SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines, 2005; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007).

Careful pre-procedure evaluation is essential to exclude preg- nancy and genital tract malignancy. Other absolute contraindica- tions include comorbidities that may increase the risk for infectious complications (e.g. pelvic inflammatory disease, salpin- gitis or endometritis, or active genitourinary infection), the pre- sence of an adnexal mass and conditions that contraindicate any endovascular procedure (e.g. reduced immune status, severe coa- gulopathy, severe contrast medium allergy, or impaired renal func- tion). The desire to avoid a hysterectomy under any circumstances is also an absolute contraindication to UAE as there is a small (,1%) risk of hysterectomy because of procedure-related compli- cations (Hovsepian et al., 2004; SOGC Clinical Practice Guide- lines, 2005).

Menopausal status is no longer considered an absolute contrain- dication to UAE as there have been reports of successful outcomes from this therapy in carefully selected post-menopausal women with fibroid-related pressure symptoms (Chrisman et al., 2007). Relative contraindications to UAE include recent use of GnRH-agonist as this drug may impact on the technical success of the procedure, and coexisting adenomyosis or endometriosis as these conditions may increase the risk of treatment failure (Hovsepian et al., 2004; SOGC Clinical Practice Guide- lines, 2005; National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2007). Patient evaluation for UAE should include hysteroscopy and/or endometrial sampling, if indicated, and imaging studies using transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasound and/or MRI (Bazot et al., 2001; Spielmann et al., 2006; Vitiello and McCarthy, 2006) to assess the uterine size and number, size and location of the fibroids, screen for adenomyosis and rule out any other signifi- cant pelvic pathology (Walker and Pelage, 2002; Pelage et al., 2005).

There are no restrictions to the size and number of fibroids that can be treated with UAE. Anatomic exclusion criteria only include submucosal fibroids that may be effectively treated with hystero- scopic resection, and pedunculated subserosal fibroids with a narrow stalk (attachment point ,50% of the diameter) because of the potential risk and complications from infarction of the stalk and subsequent fibroid detachment from the uterus (Andrews et al., 2004; Katsumori et al., 2005).

A very large fibroid uterus is not a contraindication to UAE since favourable clinical outcomes have been observed even in women with greater than 24-week pregnancy size uteri (Prollius et al., 2004). However, uterine volume reduction following UAE generally does not exceed 50%, and women with a very large uterus who consider this option should be counselled that their bulk-related symptoms may not be as well treated as their men- strual complaints.

Comparative studies

There are eight studies published that have compared the out- comes of UAE versus conventional surgical procedures for symp- tomatic fibroids (Table I).

So far, three studies have been performed in which clinical out- comes of UAE were compared with those of abdominal myomect- omy, two retrospective cohort studies (Broder et al., 2002; Razavi et al., 2003) and one prospective, but non-randomized, trial (Goodwin et al., 2006). Overall, these studies consistently reported that the two procedures were equally safe and effective in relieving fibroid-related symptoms. However, likely related to heterogen- eity in the baseline patient characteristics and in the methods and timing of follow-up, there was some discrepancy in specific outcome results (Broder et al., 2002; Razavi et al., 2003; Goodwin et al., 2006).

Broder and colleagues compared outcomes of 51 UAE patients and 30 myomectomy patients at a follow-up period ranging from 3 to 5 years (Broder et al., 2002). The investigators found no signifi- cant differences between the groups in the rates of overall symptom improvement and patient satisfaction with outcome, but the rate of subsequent interventions was higher for the UAE than for the myomectomy group (P ¼ 0.004). However, UAE patients were older (P , 0.001) and more likely to have under- gone prior surgery for fibroids (78 versus 3%, P , 0.001), suggesting they may have had more extensive disease than myo- mectomy patients.

A similar retrospective study by Razavi and colleagues reported on 67 UAE patients and 44 myomectomy patients with mean follow-up periods of 14.6 and 14.3 months, respectively (Razavi et al., 2003). Women in the UAE group were older (P , 0.05)women in the myomectomy group. In this study, the rate of improvement in menorrhagia was higher for the UAE than for the myomectomy group (92 versus 64%, P , 0.05), whereas the rate of improvement in pressure symptoms was higher for the myomectomy than for the UAE group (76 versus 91%, P , 0.05). The investigators also reported shorter hospital stays (0 versus 2.9 days, P , 0.05), faster recovery times (8 versus 36 days, P , 0.05) and a lower overall morbidity rate (11 versus 25%) for UAE than for myomectomy. Finally, they found no differ- ences between the groups in the rate of subsequent interventions.and more likely to present with menorrhagia (P , 0.05).

The multi-centre prospective study by Goodwin et al. (2006) compared the outcomes of 149 UAE patients and 60 myomectomy patients. Women in the UAE group were older (P , 0.001), had more numerous fibroids (P , 0.0001), and were more likely to present with menorrhagia (P ¼ 0.02) than women in the myomect- omy group. At 6 months, the rate of overall clinical success, defined as significant improvement in both QOL and menstrual bleeding scores, was similar for the UAE (81.2%) and the myo- mectomy group (75%). Differences between the groups were identified and included the mean hospital stay (,1 day for UAE versus 2.5 days for myomectomy, P , 0.001), the mean recovery time (14.6 days for UAE versus 44.4 days for myomectomy, P , 0.05) and the overall complication rate (22.1% for UAE versus 40% for myomectomy, P ¼ 0.01). Re-intervention rates did not differ between the groups.

To date, there have been four studies one multi-center prospec- tive (Spies et al., 2004a,b), one multi-center retrospective cohort (Dutton et al., 2007) and two RCTs (Pinto et al., 2003, and the EMMY trial published in four papers Hehenkamp et al., 2005, 2006; Volkers et al., 2006, 2007) published that compared UAE with hysterectomy. In a third RCT, outcomes of UAE were com- pared with outcomes of a mixed group of hysterectomies and myo- mectomies (Edwards et al., 2007) (Table I).

The prospective study by Spies and colleagues compared UAE versus a mixed group of hysterectomies (abdominal, laparoscopic, vaginal and laparoscopically assisted vaginal) (Spies et al., 2004b). Women undergoing UAE were more likely to have had previous fibroid surgery (P , 0.04) and had more numerous fibroids (P , 0.021) and larger mean uterine volume (P , 0.001) than hysterectomy patients. The investigators reported sig- nificant differences between the groups in the mean hospital stay (0.8 days for UAE versus 2.3 days for hysterectomy, P , 0.001) and recovery time (10.7 days for UAE and 32.5 days for hyster- ectomy, P , 0.001). At 12-month follow-up, UAE patients reported a marked improvement compared with baseline in blood loss scores (P , 0.001) and menorrhagia questionnaire scores (P , 0.001). The rate of improvement in pelvic pain at 12 months was higher for the hysterectomy than for the UAE group (98 versus 84%, P ¼ 0.021), but there were no differences between the groups in the degree of improvement in pressure symptoms, overall health assessment, and QOL scores or the rate of patient satisfaction with outcomes. The overall morbidity was higher in the hysterectomy than in the UAE group (34 versus 14.7%, P ¼ 0.01), but the incidence of major complications was similar for the two groups. Finally, there were no significant differences between the groups in the rate of subsequent interventions.

The recently published Hysterectomy or Percutaneous Emboli- sation For Uterine Leiomyomata (HOPEFUL) study was a retro- spective cohort comparing long-term safety and efficacy of UAE and hysterectomy (abdominal, laparoscopic, vaginal or laparosco- pically assisted vaginal) (Dutton et al., 2007). The study, which involved 18 hospitals in the UK, included 1108 women treated with UAE (n ¼ 649) or hysterectomy (n ¼ 459) from the mid-1990s. The average length of follow-up was 4.6 years for the UAE and 8.6 years for the hysterectomy cohort. At baseline UAE women were younger (P , 0.0001) and more likely to have had prior pelvic surgery (P , 0.0001) than hysterectomy women.

The investigators reported lower rates of overall morbid- ity and major morbidity for the UAE than the hysterectomy cohort (P , 0.001 and 0.0001, respectively) and adjusted odds ratios for UAE versus hysterectomy of 0.48 (95% CI 0.26 – 0.89) for all complications and 0.25 (95% CI 0.13 – 0.48) for major compli- cations. More hysterectomy women reported symptomatic relief (P , 0.0001) and feeling better (P , 0.0001), but patient satisfac- tion was higher with UAE than with hysterectomy (P ¼ 0.007). One hundred and nineteen women (18.3%) in the UAE cohort had a subsequent intervention (e.g. hysterectomy, myomectomy or repeat UAE) during follow-up. After adjusting for differential time of follow-up, there was a 23% (95% CI 19 – 27%) chance of requiring further treatment within the first 7 years.

The earliest of the RCTs comparing UAE and hysterectomy was small (enrolling only 57 women) and used a controversial randomized-consent methodology, in which women who were randomly assigned to hysterectomy were not informed about the study or about the possible alternative treatment (Pinto et al., 2003). The primary outcome measure was the mean length of hos- pital stay, which was shorter for the UAE than for the hyster- ectomy group (1.7 versus 5.8 days, P , 0.001). Patients in the UAE group also had shorter recovery times than women in the hysterectomy group (9.5 versus 36.2 days, P , 0.001).

The inves- tigators found no differences between the groups in the overall complication rate within the first 30 days of treatment, but hyster- ectomy women were more likely to experience major compli- cations than UAE women (20 versus 2%). At 6 months of follow-up, the clinical success rate for the UAE group, which was based on the cessation of bleeding, was 86% (31 of 37 patients). By 6 months, the rate of subsequent interventions for the UAE group was of 5.5% (2 of 36 patients).

The second RCT of UAE versus hysterectomy (abdominal, vaginal, laparoscopic or laparoscopically assisted vaginal) was the EMbolization versus hysterectoMY (EMMY) trial, which involved 28 Dutch hospitals and enrolled 177 patients (Hehenkamp et al., 2005). The primary endpoint of the study was the elimin- ation of menorrhagia after a follow-up period of 2 years, with UAE considered equivalent to hysterectomy if menorrhagia resolved in at least 75% of patients with no significant differences in major complications between the two procedures.

The first three publications from the EMMY trial reported on short-term outcomes from UAE versus hysterectomy (Hehenkamp

et al., 2005, 2006, Volkers et al., 2006). The investigators reported a shorter mean hospital stay (2 versus 5.1 days, P , 0.001) but higher rates of minor complications (58 versus 40%, P ¼ 0.024) and readmissions (11 versus 0%, P ¼ 0.003) during the first 6 weeks after discharge for the UAE group than for the hyster- ectomy group. However, there were no significant differences between the groups in the rates of major in-hospital and post- discharge complications (Hehenkamp et al., 2005). Women in the UAE group also reported significantly less pain during the first 24 h postoperatively (P ¼ 0.012) and returned to work sooner (28 versus 63 days, P , 0.001) than hysterectomy patients (Hehenkamp et al., 2006). Of note, the rate of procedural UAE failure, defined as the failure to perform bilateral UAE, reported from this trial was of 17.3% (Volkers et al., 2006), that was much higher than the failure rates previously reported in large UAE series (0.5 – 7.3%) (Spies et al., 2001a; Pron et al., 2003c; Worthington-Kirsch et al., 2005). This could be, at least partly, explained by the fact that the majority (19 of 26) of the interven- tional radiologists in the EMMY trial were relatively inexperi- enced with UAE, having performed less than 10 embolization procedures before the study started.

The fourth EMMY publication reported 2 years’ outcomes from UAE versus hysterectomy (Volkers et al., 2007). At 2 years after treatment, 23.5% (19 of 81) of UAE patients had undergone a hys- terectomy because of persistent or recurrent symptoms. There were no significant differences between the two groups in the degree of improvement compared to baseline in pain (84.9% for UAE versus 78% for hysterectomy) and pressure symptoms (66.2% for UAE versus 69.2% for hysterectomy). On the basis of these findings, the investigators concluded that, although the failure rate of UAE, defined as the necessity to perform a hyster- ectomy in the first 2 years after the procedure, stayed within the preset failure rate maximum of 25%, the 76.5% clinical success rate was much lower than results from earlier uncontrolled UAE series (Volkers et al., 2007). However, when interpreting the results from this trial, it must be taken into consideration that the 23.5% failure rate of UAE reported at 2 years was affected by 4 (4.9%) cases of bilaterally failed procedure and 10 (12.3%) cases of unilateral embolization. Since the impact of technically failed procedures on clinical outcomes was not evaluated, the degree to which the high incidence of technical UAE failure in this trial could have influenced the outcome results remains unknown.

The Randomized Trial of Embolization versus Surgical Treat- ment for Fibroids (REST), which involved 27 hospitals in the UK, compared outcomes for 106 women randomly assigned to UAE versus 51 assigned to abdominal surgery (43 hysterectomies and 8 myomectomies) (Edwards et al., 2007). The primary outcome measure was health-related QOL at 1 year, as assessed on the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form General Health Survey (SF-36) (Jenkinson et al., 1996).

The investigators found no differences between groups in QOL measures at 1 year, although women in both groups had substantial improvements in each component of the SF-36 score compared to baseline. The UAE group had shorter hospital stays (1 day compared to 5 days, P , 0.001) and recovery times (20 days compared with 62 days, P , 0.001) than the hysterectomy group. There were no differences between the groups in the rate of major complications (15% for the UAE and 20% for the surgical group). Of note, 3 (2.8%) of the major complications in the UAE group were cancers, which were highly unlikely to be related to treatment. At 1 year of follow-up, 10 (9%) women in the UAE group had required additional interventions (hysterectomy or repeated UAE) to treat persistent or recurrent symptoms. Of these re-interventions, two (1.9%) were due to bilaterally failed UAE procedures.

Overall, results from published RCTs yielded consistent evi- dence that UAE offers an advantage over conventional surgery for fibroids in terms of shorter hospital stay and quicker return to daily activities. Clinical outcomes after embolization also appear to be similar to that of surgery, with most women reporting symptom control and satisfaction with outcome up to 2 years after treatment. Overall morbidity and major complication rates associ- ated with UAE also appear to be similar to those with surgery.

To date, there have been eight published studies analysing the cost and cost-effectiveness of UAE in comparison with standard surgical procedures (Table II) (Al-Fozan et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2002; Pourrat et al., 2003; Beinfeld et al., 2004; Edwards et al., 2007; Dembek et al., 2007; Goldberg et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007). In these studies, hospital costs associated with UAE were lower, largely because of shorter lengths of stay, which compensated well for the higher physicians’ fees and imaging costs than those of surgery (Al-Fozan et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2002; Dembek et al., 2007; Goldberg et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007). Comparative cost-effectiveness analyses also showed that UAE was more cost-effective than surgery (Pourrat et al., 2003; Beinfeld et al., 2004; Edwards et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007), even when the costs of repeat procedures and associ- ated complications were factored in (Wu et al., 2007).

Reproductive outcomes

The effect UAE may have on subsequent fertility and pregnancy remains understudied. This is the reason why this therapy is still regarded by most as relatively contraindicated in women who wish to preserve their fertility (Hovsepian et al., 2004; ACOG Committee Opinion, 2004; SOGC Clinical Practice Guidelines, 2005). Transient or permanent amenorrhea with other symptoms of ovarian failure has been reported in up to 5% of women after UAE (Spies et al., 2001b; Walker and Pelage, 2002; Pron et al., 2003a). Most of these cases have been in women over the age 45, but there have been anecdotal reports of ovarian failure in younger women (Chrisman et al., 2000; Walker and Pelage, 2002). The most likely cause is believed to be non-target ovarian embolization via the utero-ovarian collaterals, potentially result- ing in ovarian ischaemia and loss of ovarian follicles (Payne et al., 2002; Tulandi et al., 2002). Because of these observations, concern has been raised about the possible risk of premature ovarian failure in premenopausal women undergoing the pro- cedure. To address this issue, several studies evaluated the effects of UAE on ovarian reserve by measuring basal (cycle day 3) serum FSH levels before and after treatment in women of different ages (Spies et al., 2001b; Ahmad et al., 2002; Healey et al., 2004; Hovsepian et al., 2006). All these studies reported no significant changes in basal FSH in most women after UAE (Spies et al. 2001b; Ahmad et al., 2002; Healey et al., 2004;Hovsepian et al., 2006).

A prospective study of 20 regularly cycling women undergoing embolization specifically addressed the issue of the impact of UAE on ovarian reserve in younger women (up to age 40) (Tropeano et al., 2004). Results of this study indicated no change in ovarian reserve, as assessed by basal FSH and estradiol levels and ultrasound-based ovarian volume and antral follicle count, up to 12 months after the procedure (Tropeano et al., 2004). Although these findings are reassuring, larger series with longer- term follow-up periods are clearly needed to make conclusive statements on the potential subclinical impact of UAE on ovarian function.

As a result of the abundant collateral arterial circulation, normal uterine tissue usually recovers from the reduction in uterine blood flow induced by bilateral UAE. Ultrasound and MRI follow-up examinations have documented rapid revascularization of the normal myometrium and an essentially normal appearance of the endometrium at 3 – 6 months after embolization (deSouza and Williams, 2002; Pelage et al., 2004). However, there have been case reports of uterine necrosis (Godfrey and Zbella, 2001; Shashoua et al., 2002; Gabriel et al., 2004; Torigian et al., 2005), uterine wall defect (De Iaco et al., 2002) and endometrial atrophy following UAE (Tropeano et al., 2003). As a result, there is still a concern for potential effects of the procedure on the integrity of the myometrium and endometrium.

Nevertheless, published series of uncomplicated pregnancies and normal deliveries after UAE continue to increase (Table III) (Ravina et al., 2000; McLucas et al., 2001b; Carpenter and Walker, 2005; Pron et al., 2005; Walker and McDowell, 2006; Holub et al., 2007). These reports demonstrate that women can conceive and carry a pregnancy successfully to term after UAE. They also demonstrate higher rates of spontaneous abortion (Ravina et al., 2000; McLucas et al., 2001b; Carpenter and Walker, 2005; Pron et al., 2005; Walker and Mc Dowell, 2006; Holub et al., 2007), preterm delivery (Ravina et al., 2000; Carpenter and Walker, 2005; Pron et al., 2005; Walker and McDowell, 2006; Holub et al., 2007), Caesarean section (Ravina et al., 2000; McLucas et al., 2001b; Carpenter and Walker, 2005; Pron et al., 2005; Walker and McDowell, 2006; Holub et al., 2007), abnormal placentation (Pron et al., 2005; Carpenter and Walker, 2005; Walker and Mc Dowell, 2006) and post-partum haemorrhage (Carpenter and Walker, 2005; Pron et al., 2005; Walker and McDowell, 2006; Holub et al., 2007) following UAE compared to the general population.

However, interpretation of the data from these UAE cohorts is difficult because of confounding factors such as the advanced maternal age, prior reproductive issues and the severe fibroid disease present in most patients. It must be also remembered that while UAE is effective at shrinking fibroids and improving symptoms, it does not remove fibroids, and there are known associations between fibroids, pregnancy loss, and certain pregnancy complications (Bajekal and Li, 2000; Coronado et al., 2000). To what extent pre-embolization fibroid characteristics may influence subsequent reproductive outcome remains unknown. Results of a retrospective MRI analysis of fibroid location in a cohort of 51 women achieving pregnancy after UAE showed that all subtypes of fibroids were present in women achieving a live birth (n ¼ 35) versus those who did not (n ¼ 16) (Walker and Bratby, 2007). On the basis of these findings, the authors suggested that the location of fibroids treated with UAE does not have a negative impact on subsequent fertility (Walker and Bratby, 2007). However, as pointed out by the authors, this was a small retrospective study which was further limited by the pre- sence of multiple fibroids in most women, which made it difficult to establish effects of individual fibroids in specific locations.

Whether pregnancy outcomes after UAE are different from those after myomectomy remains to be determined. One study comparing reported pregnancy outcomes after UAE versus those from a published series of pregnancies after microscopical mys- mectomy found that pregnancies after embolization were associated with a significantly higher risk of preterm delivery and malpresentation (Goldberg et al., 2004). However, the reliability of these conclusions can be questioned as this study was subjected to a wide range of substantial biases, including heterogeneity in the demographics of the populations that were compared and the inability to control for other confounding variables such as the fibroid size, number and location (Goldberg et al., 2004). Clearly, well-designed prospective case– control studies are necessary to draw any conclusions about the relative impact of UAE and more conventional uterus-preserving procedures on pregnancy outcomes.

To date, only one randomized trial has been published compar- ing outcomes of UAE and myomectomy (abdominal or laparo- scopic) in young women (up to age 40) seeking fertility preservation (Mara et al., 2006, 2007). Six-month ultrasound follow-up showed no significant uterine pathology in 43% (13 of 30) of women assigned to UAE compared with 82% (27 of 33) of women assigned to myomectomy (Mara et al., 2006). The investigators also reported a 37% re-intervention rate in the UAE group compared with 6.1% in the myomectomy group by 6 months after treatment (Mara et al., 2006). In a follow-up to the initial results from this trial, the investigators reported on reproductive outcomes in a cohort of 66 women assigned to UAE (n ¼ 26) or myomectomy (n ¼ 40) who tried to conceive after treatment (Mara et al., 2007).

At a mean follow-up of 25 months, there were more pregnancies (n ¼ 33) and deliveries (n ¼ 19) and fewer abortions (n ¼ 6) in the myomectomy than in the UAE group (17 pregnancies, 5 deliveries and 9 abortions) (P , 0.05), but obstetrical and perinatal results were similar in both groups. On the basis of these findings, the authors concluded that compared with UAE, myomectomy appears to have superior reproductive outcomes within 2 years of treatment (Mara et al., 2007). However, due to the small sample size, this study lacked sufficient power to appropriately assess the relative impact of the procedures on fertility rates and pregnancy outcomes. Overall, the currently available data on fertility and pregnancy after UAE are insufficient to routinely offer UAE as an alterna- tive to myomectomy to women who wish to preserve, or enhance, their fertility. However, for women with prior myo- mectomy, very large or difficult-to-remove fibroids, or in whom surgery is contraindicated UAE may be a safer approach than myomectomy.

In summary, UAE appears to be an excellent treatment option for most women with symptomatic fibroids, especially for those who no longer desire fertility but wish to avoid surgery or are poor surgical risks. Appropriate pre-procedure selection and careful follow-up of patients are necessary to optimize clinical outcomes from this therapy. For this reason, an interdisciplinary approach involving both gynaecologists and interventional radiol- ogists, with gynaecologists taking a pivotal role in the selection, co-management and follow-up of patients undergoing UAE should be implemented into clinical practice.

Transvaginal temporary uterine artery occlusion

Transvaginal uterine artery occlusion is an alternative method of reducing blood flow in the uterine arteries for the treatment of uterine fibroids. It is based on the theory that fibroids are killed by temporary uterine artery occlusion through a mechanism of transient uterine ischaemia (Burbank and Hutchins, 2000; Lichtin- ger et al., 2003). The procedure is performed by placing a Doppler ultrasound-enabled transvaginal clamp (Flostat, Vascular Control Systems, San Juan Capistrano, CA, USA) in the vaginal fornices and, guided by Doppler ultrasound auditory signals, positioning it to occlude the uterine arteries by mechanical compression against the cervix. The clamp is left in place for 6 h and then removed.

Preliminary clinical feasibility studies in a total of 75 women (Dickner et al., 2004; Istre et al., 2004; Garza-Leal et al., 2005; Lichtinger et al., 2005; Vilos et al., 2006) reported few procedure-related complications, including two cases of hydrone- phrosis requiring temporary stenting, and successful short-term outcomes, with a reduction of 40 – 50% in uterine and fibroid volume and symptomatic improvement in 80 – 90% of patients at 6-month follow-up. Potential advantages of this technique over UAE are no radi- ation exposure, no risk of non-target embolization, and the absence of significant post-procedure pain in most patients. However, although reported short-term results of transvaginal occlusion are similar to those of UAE, long-term outcomes might not be as favourable since the degree of tissue ischaemia affected by this procedure is dramatically less than with UAE. It appears, therefore, that long-term studies are needed to discern whether transvaginal uterine artery occlusion will lead to durable results, and to compare it with UAE.

MRI-guided focused ultrasound

MRI-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) is a new, minimally invasive method of thermal ablation for treating fibroids that received the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2004. With this technique, high-intensity ultrasound waves pass through the anterior abdominal wall and converge into a precise target point within the fibroid to cause a temperature rise (55 – 908C) sufficient to induce coagulative necrosis within a few seconds. Concurrent MRI allows accurate tissue targeting and real-time temperature feedback, thereby achieving controlled localized thermal ablation (Stewart et al., 2003; Tempany et al., 2003; Hindley et al., 2004). The procedure is performed with a device (ExAblate 2000; InSightec, Haifa, Israel) that integrates a standard MRI unit with a focused piezoelectric phased-array transducer in the MRI table. During treatment, which is performed under intravenous conscious sedation, the patient is positioned prone on the MR table with the abdomen directly above the transducer.

The treatment itself consists of consecutive exposures to focused ultrasound energy (sonications), each one lasting ~20 s and resulting in a small (~0.5 cm3) bean-shaped ablated volume. Between sonications there is a pause of ~90 s to elapse for the tissue to return to its baseline temperature. Multiple sonica- tions are required to cover the entire target volume, which is typi- cally limited to a maximum of 150 cm3 of tissue, and total procedure time is usually over 3 h. Common symptoms during the procedure are short-term lower abdominal pain, leg pain and buttock pain. Patients are usually discharged home ~1 h after the end of the procedure and return to usual activities, on average, within 48 h (Stewart et al., 2003). To date, publications on MRgFUS have been case series showing technical feasibility (Stewart et al., 2003; Tempany et al., 2003) and short-term outcomes (Hindley et al., 2004; Hesley et al., 2006; Smart et al., 2006; Stewart et al., 2006). The pivotal trial of MRgFUS for fibroids was a multi-center study including 109 premenopausal women with fibroids smaller than 10 cm in diameter (Stewart et al., 2006). During the pro- cedures, less than 10% (on average, 25 cm3) of the targeted fibroid volume was treated, and most patients had only one fibroid treated. The procedure was relatively well tolerated, with only 16% of women reporting severe pain during the treatment and 8% reporting severe-to-moderate pain after the procedure.

There were relatively few serious complications including one case of sciatic nerve palsy that resolved by 12 months, superficial skin burns in 5% of patients and one case of skin burn that caused ulceration. At 6 months, despite only modest reductions in targeted fibroid volumes (on average, 13.5%), 77 (71%) of the 109 treated patients showed a significant symptom improvement, as measured by the symptom severity score of the UFS-QOL ques- tionnaire (Spies et al., 2002a). At 12 months, with only 82 women of the original cohort available for evaluation, 51% (42 of 82) reported continued symptom control, whereas 28% (23 of 82) had sought alternative surgical therapy.

Better outcomes in terms of rates of symptom relief (83% at 6 months and 89% at 12 months of follow-up) and reductions in the targeted fibroid volume (on average, 21% at 6 months and 37% at 12 months) were reported in 49 women with fibroids greater than 10 cm in diameter, who were pretreated with GnRH-agonist for 3 months (Smart et al., 2006). On the basis of these findings, the authors concluded that reducing fibroid vascu- larity by pre-procedural GnRH-agonist therapy may enhance the thermoablative effect of MRgFUS, resulting in a greater clinical response to treatment (Smart et al., 2006).

Changes in treatment protocol, with decreased restrictions on treatment parameters, have been reported to increase effectiveness of MRgFUS (Fennessy et al., 2007). Recently published data on 359 women completing 24-month follow-up in all clinical trials of MRgFUS showed greater symptom reduction (P , 0.001) and lower risk of additional treatments (P ¼ 0.001) over the first 24 months for women receiving more aggressive treatment (more than 20% of the fibroid volume ablated)compared to those having less extensive treatment (20% or less of the fibroid volume ablated) (Stewart et al., 2007).

As the total number of cases treated by MRgFUS is quite small when compared with UAE, it is difficult to draw inferences about the relative pros and cons of these two minimally invasive options. Advantages of MRgFUS are no radiation exposure, no risk of non- target embolization, and the absence of significant post-procedure pain, which eliminates the need for an overnight stay and likely speeds the return to daily activities. However, compared with UAE, MRgFUS has more numerous restrictions to the size and number of fibroids that can be treated as the time required to perform the procedure is volume dependant, and it is also less effective in reducing uterine and fibroid size. In addition, several patient characteristics including fibroids close to neurovascular bundles or sensitive organs, such as bladder and bowel, and those outside the image area, and the presence of bowel loops or abdominal wall scars in the projected ultrasound beam pathway may preclude patients from undergoing treatment (Tempany et al., 2003).

Questions still remain to be answered regarding the safety of this procedure. From a preliminary feasibility study (Tempany et al., 2003), it is apparent that, likely related to collateral thermal injury, the area of tissue necrosis measured by histopathologic examination of post-procedure hysterectomy specimens is on average 3-fold higher than the treatment volume predicted by MRI. This not only seems to argue against the notion of ‘focused’ delivery of ultrasound energy but also raises concerns about the risk of expansion of the thermal injury beyond the boundary of the fibroid into normal myometrium or extrauterine structures.

Another unresolved issue with MRgFUS concerns the durability of clinical improvement over time. Since only a small amount of fibroid tissue is usually ablated, patients undergoing the procedure may be at risk for re-growth of the residual viable fibroid tissue and recurrence of symptoms. Overall, the data to date suggest that MRgFUS holds promise for incisionless surgery for appropriately selected patients with symp- tomatic fibroids, but still are too few to draw conclusions about the safety and long-term effectiveness of this treatment modality.

New medications

All medications currently available for fibroid treatment including GnRH-agonist and sex steroids are unsuitable for long-term use because of their significant side-effects (Young et al., 2004). In recent years, new medications have been introduced that offer the promise of practical, long-term, medical therapy for sympto- matic fibroids. To date, the most encouraging results in terms of fibroid volume reduction, symptom relief, and compliance with long-term administration have been obtained with mifepristone, a progesterone receptor antagonist, and asoprisnil, a selective pro- gesterone receptor modulator. Mifepristone has been the first available active antiprogestin (Philibert et al., 1981; Philibert, 1984). It has been shown to decrease fibroid size and blood flow to the fibroids (Murphy et al., 1993, 1995; Reinsch et al., 1994). Early studies of women with symptomatic fibroids reported that daily adminis- tration of mifepristone at doses ranging from 5 to 50 mg for 3 to 6 months resulted in a 26 – 74% reduction in fibroid volume and a decrease in the prevalence and severity of fibroid-related symptoms, including menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea and pelvic pressure (Steinauer et al., 2004). However, a high incidence (28%) of endometrial hyperplasia was observed in patients screened with endometrial biopsies (Steinauer et al., 2004).

A prospective, randomized, controlled trial comparing the out- comes of 5 mg per day to 10 mg per day of mifepristone reported significant reductions compared with baseline in uterine volume and menstrual blood loss in both groups at 6 months, with no sig- nificant differences between the groups (Eisinger et al., 2003). In a follow-up of the original trial, the investigators assessed the occur- rence of endometrial hyperplasia after 18 months of mifepristone therapy in 21 of the 40 original women in the study (Eisinger et al., 2005). They found no case of hyperplasia at 6 and 12 months among women treated with 5 mg, and a 14% rate at 6 months and 5% rate at 12 months for the group treated with 10 mg (Eisinger et al., 2005).

More recently, in a randomized, double-blinded, placebo- controlled trial including 42 women with symptomatic fibroids, treatment with mifepristone 5 mg per day for 26 weeks led to a 47% reduction in fibroid size and a significant improvement in fibroid-related symptoms and QOL scores (Fiscella et al., 2006). By 12 months, 9 (41%) of 22 women randomized to mifepristone had become amenorrheic (Fiscella et al., 2006). The drug was well tolerated, and no endometrial hyperplasia was noted in any partici- pant (Fiscella et al., 2006). Although these data are very encoura- ging, further studies in larger samples with longer periods of treatment are needed to reliably assess the long-term safety and efficacy of this drug.

Another promising medication for fibroid treatment is asoprisnil, a selective progesterone receptor modulator with mixed agonist/ antagonist activity. This drug has been shown to inhibit prolifer- ation and induce apoptosis in uterine fibroid cells (Chen et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2006). In addition, it has an inhibitory effect on the endometrium as a result of suppressed endometrial angiogen- esis and/or function of the spiral arteries (Chwalisz et al., 2004, 2005). Small observational studies of women with symptomatic fibroids showed that daily treatment with asoprisnil at doses ranging from 5 to 25 mg for 3 months reduced fibroid volume in a dose-dependent manner and suppressed both abnormal and normal uterine bleeding, with no effects on circulating estrogen levels and no breakthrough bleeding (Chwalisz et al., 2005).

In a recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial involving 129 women, a 3-month treatment with asoprisnil doses of 5, 10 and 25 mg daily suppressed uterine bleeding in 28, 64 and 83% of women, respectively, and reduced fibroid volume and fibroid-related pressure symptoms (Chwalisz et al., 2007). Asoprisnil treatment was associated with follicular-phase estrogen concentration and minimal hypoestrogenic symptoms (Chwalisz et al., 2007). These promising findings warrant replication through larger controlled trials over extended treatment intervals.

Conclusions

Expanding non-surgical treatment options for fibroids are advan- cing care for women, who are now increasingly willing to be treated while keeping the constraints and sequelae of treatment to a minimum. At the same time, the new possibilities afforded by these minimally invasive options do raise challenging questions about changing indications for surgery in the management of uterine fibroids.

So far, however, the availability of alternative treatments has failed to substantially change everyday clinical practice, and the majority of women with symptomatic fibroids are still managed surgically. This is, at least partly, because some of the newer approaches including MRI-guided focused ultrasound and tempor- ary uterine artery occlusion are still investigational, which poses the problem of their long-term safety and efficacy compared with standard surgical treatment.It is more difficult to be sure of the reasons why UAE remains underused in spite of the accumulating good-quality evidence to support its safety and effectiveness. The major issues, however, seem to be about increasing the gynaecologists’ awareness and acceptance of UAE as a viable treatment option for fibroids and improving the collaboration between gynaecologists and interven- tional radiologists to facilitate optimal care for patients.

In addition to these minimally invasive options, there is growing interest in pharmacological therapies, including novel agents such as TAK-243 MLN7243 E1 Activating inhibitor nature medicine, which may offer new avenues for treatment. TAK-243 is an investigational drug that targets the cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin ligase complex, a key regulator of protein degradation. By modulating this pathway, TAK-243 holds potential not only in oncology but also in treating fibroid-related cellular abnormalities. While still in the early stages of research, the drug has shown promising effects in reducing cell proliferation and inhibiting the growth of certain tumors. Future clinical trials may reveal its efficacy in managing uterine fibroids, especially in women who wish to preserve fertility or seek alternatives to invasive procedures. As with other investigational treatments, further data is needed to fully understand its safety and long-term effects, but TAK-243 (also known as MLN7243) could represent a significant step forward in medical management for uterine fibroids, particularly in combination with existing non-surgical techniques.TAK-243 is a first-in-class inhibitor of the ubiquitin-activating enzyme (UAE). By disrupting the protein degradation pathway, it induces proteotoxic stress and apoptosis in tumor cells. Its potential application in treating fibroids is currently being explored in research settings, such as those documented by the National Institutes of Health (ClinicalTrials.gov), to determine if it can effectively reduce fibroid volume without the need for invasive surgery.